Fact checking Moravec's paradox

The famous aphorism is neither true nor useful

I have launched a YouTube channel in which I analyze AI developments from a normal technology perspective. This essay is based on my most recent video in which I did a deep dive into Moravec’s paradox, the endlessly repeated aphorism that tasks that are hard for humans are easy for AI and vice versa.

Here’s what I found:

Moravec’s paradox never been empirically tested. (It’s often repeated as a fact by many AI researchers, including pioneers I know and respect, but that doesn’t mean I’ll take their claims at face value!)

It is really a statement about what the AI community finds it worthwhile to work on. It doesn’t have any predictive power about which problems are going to be easy or hard for AI.

It comes with an evolutionary explanation that I find highly dubious. (AI researchers have a history of making stuff up about human brains without any relevant background in neuroscience or evolutionary biology.)

Moravec’s-paradox-style thinking has led to both alarmism (about imminent superintelligent reasoning) and false comfort (in areas like robotics).

To adapt to AI advances, we don’t need to predict capability breakthroughs. Since diffusion of new capabilities takes a long time, that gives us plenty of time to react — time that we often squander, and then panic!

Watch the full argument here or read it below.

Every week brings new claims about AI advances. How do we know what’s coming next? Could AI predict crime? Write award-winning novels? Hack into critical infrastructure? Will we finally have robots in our home that will fold our clothes and load our dishwashers?

What will AI advances mean for your job? What will it mean for the social fabric? It’s hard to deal with all this uncertainty. If only we had a way to predict which new AI capabilities will be developed soon and which ones will remain hard for the foreseeable future.

Historically, AI researchers’ predictions about progress in AI abilities have been pretty bad. We don’t really have principles that describe which kinds of tasks are easy for AI and which ones are hard.

Well, we have one — Moravec’s paradox. It refers to the observation that it’s easy to train computers to do things that people find hard, like math and logic, and hard to train them to do things that we find easy, like seeing the world or walking.

It comes from the 1988 book Mind Children by Hans Moravec, who was — and is — a robotics researcher. He wrote:

It is comparatively easy to make computers exhibit adult level performance on intelligence tests or playing checkers, and difficult or impossible to give them the skills of a one-year-old when it comes to perception and mobility.

In the early days of artificial intelligence, researchers focused on chess and other reasoning tasks, since these were thought to be some of the hardest and what made us uniquely human. But funnily enough, if you want to build a robot that can defeat human grandmasters, figuring out which moves to make is the easy part. Physically making the moves on the chessboard is the hard part. This is pretty well known today, so Moravec’s paradox seems to make a lot of intuitive sense.

If Moravec’s paradox is true, the implications would be amazing. If we want to know which AI capabilities might be built next, we just have to see how hard they are for humans. So scientific research will get automated before folding clothes, and so on.

But here’s the thing — Moravec’s paradox has never been fact checked. And that’s despite videos with hundreds of thousands of views, and TED talks all repeating it as a fact. When I dug into the evidence behind the so-called paradox, I found something surprising.

In this essay I’ll discuss why the theory and evidence behind the paradox are flaky. Then I’ll explain why simplistic predictions about what is easy or hard for AI have misled AI researchers and tech leaders. It has led to alarmism on the one hand and false comfort on the other hand. (Now there’s a paradox.) And finally I’ll answer the question, if we can’t rely on Moravec’s paradox, then how should we prepare for AI advances and their impacts?

The evidence behind the paradox is flaky

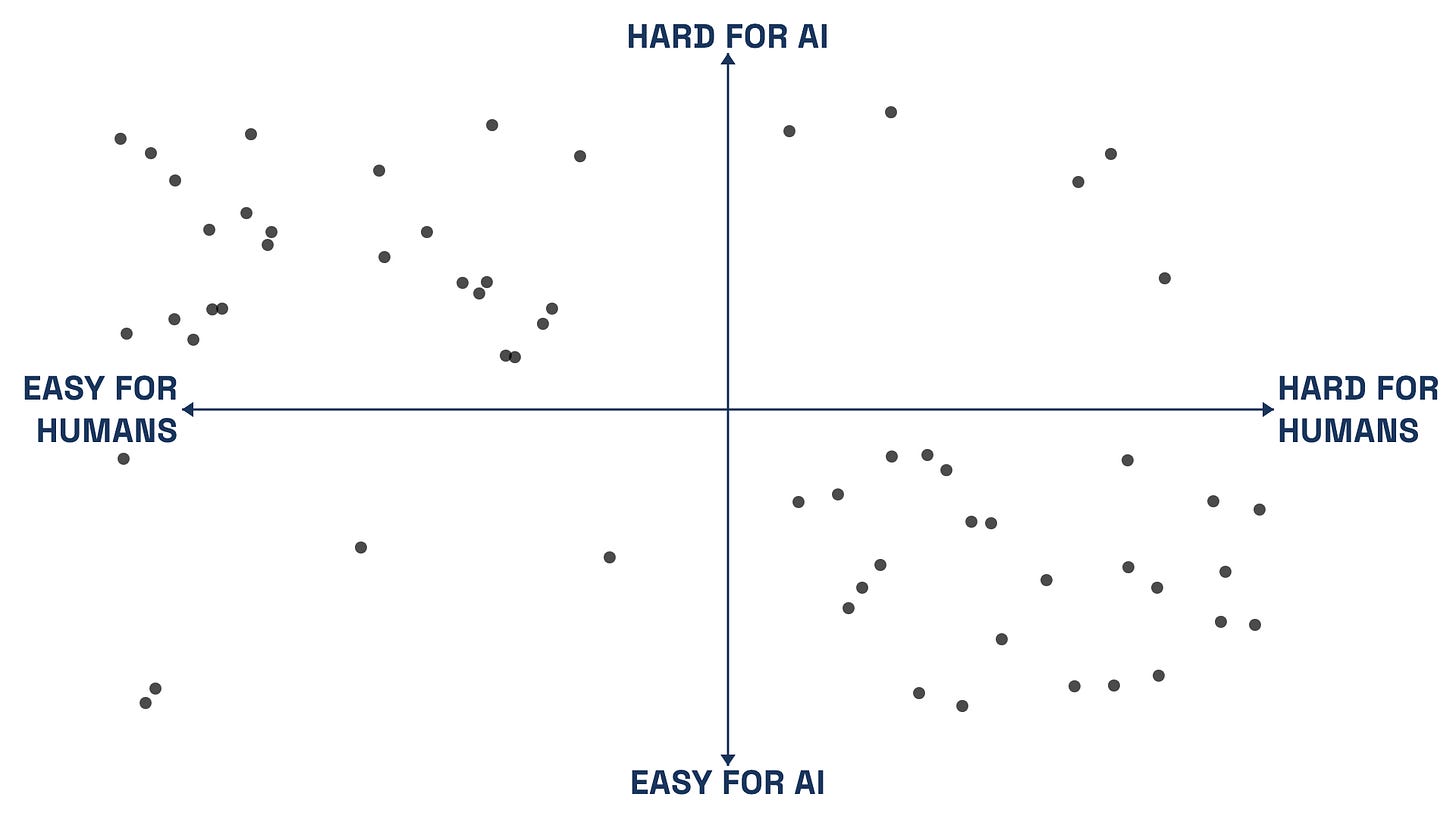

How would we test Moravec’s paradox? We could take some sample of the tasks that are out there, determine how hard they are for people, how hard they are for AI, and make a graph. If we saw something like this, the paradox would be confirmed.

But here’s the problem: Which set of tasks should we consider for our analysis? When AI researchers say Moravec’s paradox checks out, they are implicitly limiting their focus to problems that are considered interesting in the AI research community.

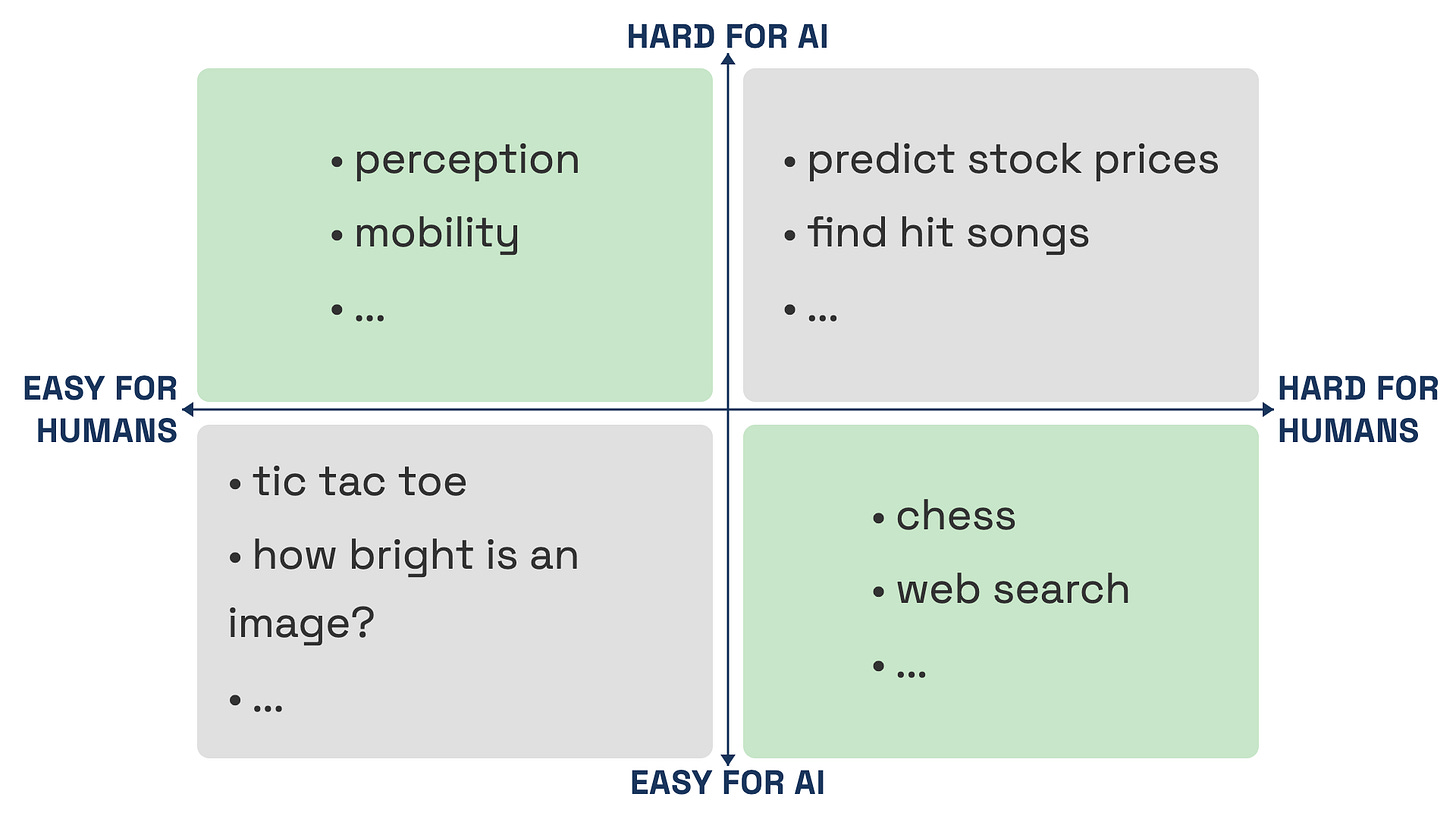

There are an endless number of tasks that are easy for both humans and AI, but they are not interesting. How bright is an image? How to play tic tac toe? Thousands of these tasks get solved by programmers on a daily basis and coded into AI systems, and when people do so, they don’t make a fuss about them.

There are also an endless number of tasks that are hard for humans and, as far as anyone knows, are also hard for AI. Identifying hit songs; predicting stock prices; cracking as-yet-undeciphered ancient scripts; even build a Dyson sphere. These are so hard that there is essentially no progress on these problems, although some of them attract junk research that tends to quickly get debunked. So these problems also don’t tend to get talked about as much.

In fact, there are thousands of problems that computer scientists have proved to be “NP-complete”, which means we have strong mathematical reasons to think they will forever be hard for AI, so serious AI researchers don’t tend to work on them. They work on easier, approximate versions of the problems instead.

The other two quadrants of the chart are different. On the top left, tasks like playing soccer, that are easy for humans but currently hard for AI, are extremely interesting to AI researchers. That’s because we know it’s possible to teach AI these skills, but we haven’t yet managed to do so, which makes them great tests for AI progress.

On the bottom right, problems that are hard for humans but easy for AI, such as searching the web, are also interesting. These capabilities tend to greatly augment human productivity. Even though they are in some sense “easy”, the industry invests a lot in making web search and other tools work as effectively, quickly, and cheaply as possible. So research on these tasks is a big driver of AI progress.

In short, when you’re thinking about the space of all possible tasks, if you basically ignore two quadrants of your 2x2 matrix because they are not interesting, then of course it will seem like what you’re left with shows a strong negative correlation between the two axes.

A flawed evolutionary argument

To be clear, the reason AI researchers are drawn to Moravec’s paradox isn’t because it is empirically backed. It’s because it comes with an intuitively appealing story. In his book, Moravec provided this explanation:

Encoded in the large, highly evolved sensory and motor portions of the human brain is a billion years of experience about the nature of the world and how to survive in it. The deliberate process we call reasoning is, I believe, the thinnest veneer of human thought, effective only because it is supported by this much older and much more powerful, though usually unconscious, sensorimotor knowledge. We are all prodigious olympians in perceptual and motor areas, so good that we make the difficult look easy. Abstract thought, though, is a new trick, perhaps less than 100 thousand years old. We have not yet mastered it. It is not all that intrinsically difficult; it just seems so when we do it.

And then Moravec praises reasoning systems like STRIPS from the 1970s, and this is the kind of thing he has in mind when he says that reasoning is easy for AI. These are purely symbolic systems that solve problems like how to put blocks on top of each other in a certain way.

But AI researchers have learned a lot in the half century since the heyday of STRIPS and other such reasoning programs. They seem quite quaint today. What we’ve learned is that symbolic reasoning only works well in closed and extremely narrow domains like chess with a fully specified set of rules. When you apply them to real-world problems they are brittle and go off the rails quickly.

Over the decades there have been many other failures of reasoning systems, like IBM’s Watson, that excelled in narrow demonstrations but failed when you tried to use them in real-world settings that could depart from what they are trained for.

Today, it is widely recognized that reasoning in open-ended settings requires common-sense knowledge. But common sense is one of the so-called easy-for-humans-but-hard-for-AI areas according to acolytes of Moravec’s paradox. In other words, AI reasoning isn’t easy after all.

And sure enough, AI reasoning in a way that can replace human expertise, in open-ended domains like law or scientific research, is still very much unsolved.

If I were to speculate where Moravec’s evolutionary argument goes wrong, it would be this: Reasoning might be new from an evolutionary perspective, but it builds on the things that animal brains have learned to do over hundreds of millions of years. This much Moravec acknowledges. But maybe there isn’t a separate skill called “abstract” reasoning that can be learned separately without all of this infrastructure.

How simplistic models have misled AI researchers and tech leaders

Unfortunately, partly because of the misconception in the AI world that reasoning is a separate skill that’s easy for computers, there is a widespread belief that AI will soon be superhuman at things like scientific research or operating a company or even running a government. In my experience, many researchers tend to generalize from AI success at chess and other closed domains to these kinds of open-ended domains.

So AI leaders promise that investing trillions into data centers will lead to a cure for cancer and various other downstream benefits, without stopping to think about how these inputs will translate into the desired outputs. It also leads them to support some extreme policies, such as investment in AI science at the expense of human scientists, and warning policymakers to prepare for a white collar bloodbath. It also leads to the fear that leaders such as politicians or CEOs military generals will soon have no choice but to delegate important decisions to AI because it will be superhuman at reasoning.

Maybe... or maybe it’s all a myth. There may not even be one general skill called reasoning.

Maybe the limits to reasoning are actually things like the lack of verifiers. That is, AI can’t get that good at legal reasoning unlike reasoning in chess, because there is no way for AI to write millions of legal arguments and get immediate and accurate feedback on which ones are good and which ones aren’t, analogous to the way AI gets good at chess.

Maybe it’s partly due to the limits of real-world knowledge. That is, AI can’t quickly become superhuman at medical reasoning because it is limited by the available medical knowledge in the world.

In other words, the same factors that pose limits to human reasoning also pose limits to AI reasoning. In this view, the answer has nothing to do with biology.

Much of my writing is based on the idea that superhuman AI reasoning is a myth. Of course, you don’t have to accept this. But when you hear these predictions of imminent superintelligence, it’s helpful to understand the underlying mental model that many people in the AI field have. And it’s definitely useful to know that we have five or six decades of evidence that whether a skill such as reasoning is easy or hard for AI can depend a lot on whether you’re talking about a closed domain or an open domain.

Now let’s look at the other side of the coin. Some AI capabilities are predicted to be hard because of Moravec’s paradox. Most frequently, it’s robotics.

Just as people say we have to worry about job losses and safety implications of breakthroughs in reasoning, they’ll say we don’t have to worry about job losses and safety risks of breakthroughs in robotics. It’s a hard problem, so improvements won’t happen overnight.

Unfortunately, this is false comfort. I could be wrong about what I said about reasoning earlier, and there could be a breakthrough tomorrow. Similarly, these researchers could be wrong about robotics and there could be a breakthrough tomorrow.

In fact, there is another “hard problem” for AI that used to be invoked to explain Moravec’s paradox, which is computer vision, and it doesn’t get invoked anymore, and that’s because there was in fact a breakthrough around 2012 / 2013 when AI performance at tasks like object recognition shot up dramatically due to deep learning. The reason it even took that long is it required the use of GPUs and the idea of using GPUs for AI only began around that time.

The scientific ideas behind deep learning had largely been established in the 1980s — before Moravec published his book — he just didn’t know it yet.

Conclusion: if not Moravec’s paradox, then what?

There’s a reason why rules of thumb like Moravec’s paradox are so tempting. It’s because we assume that if there were an AI capability breakthrough, there would be rapid societal effects such as job losses, so we should be prepared in advance.

But this isn’t actually true. Even breakthrough technologies take a long time to be successfully commercialized and deployed. In fact, breakthrough technologies may especially take a long time to be deployed, because the supporting infrastructure just isn’t there. There’s a famous case study of why it took 40 years for electric power to replace steam power in factories.

Take self-driving cars. Waymo started testing them on public roads more than 15 years ago.

There was little reason to doubt that this technology would one day be viable, and that it would have good and bad effects. Policymakers should have been preparing and figuring out how to compensate workers who stood to lose out.

Instead, people are only now waking up to the reality now that these cars and trucks are already on the road, and are pushing policies like banning them. Keep in mind that a million people per year die in car accidents worldwide, and self-driving cars are already much safer than human drivers.

A recurring theme of my work on AI is the difficulty of prediction — both the use of AI itself for prediction and predicting the future of AI capabilities and impacts.

Instead of relying on prediction, we should get better at shaping and adapting to the tech that we actually know for sure is coming. It is psychologically hard to let go of our need to want to know the future, but if we give up this false comfort we can build a much more resilient society.

Other videos

I have published three full-length videos so far, and regularly publish short videos. Subscribe here.